This is a short biography of Arcangelo (1780-1862), written by his son Don Paolo.

It was transcribed manually by my uncle John Pullicino into English. The translated text is given below, to which I have added chapter headings not in the original text for the sake of readability on this website. If you wish to read the original print copy with translation and footnotes then please view the PDF (11MB).

Chapter 1: Introduction

I take up the writing of this brief account for no reason other than as a small tribute of gratitude to a revered parent. I am drawn to this task by the benefit which the nation may derive from these memoirs, free of posturing or self interest, and offered humbly and with a proud heart. . Tireless in the cultivation of the arts, ready to promote the welfare of his own country, and highly pious and charitable in his private deeds: these are the chief characteristics which summarise the life of Dr PULLICINO.

His particular attachment to letters emerged through his studies as a youth in Rome at the Collegio Romano, through the many poetic works he wrote in various academies, as well as through private literary exercises, which even in old age kept him endlessly occupied. .

He promoted the well-being of his own country with his vigorous practise of the medical profession in the district of Zebbug during the plague of 1813, with the prominent role he played in the management of the demonstrations of the Maltese populace, which produced the political concessions initiated by the enquiry started in 1837, and with the independent cooperation he rendered to the Governor in the inaugural session of the new Council, established in January 1850. . Finally, he showed himself to be singularly pious and charitable with the not so common practice of the two great Christian virtues, prayer and almsgiving (1).

For the moment we will cover in detail the main features of his life; as these best witness the man he was.

Chapter 2: Education

Dr PULLICINO was born at Zebbug on 5th October 1780: and he was brought into the midst of a family which was well regarded in that county. His father, Dr Gabriele, a physician, was outstanding as much for science as for nobility of character: his two brothers, priests, were even more distinguished, Don Giuseppe for having facilitated the foundation and creation of the Hospital of San Giuseppe in that same village, and Don Pietro Paolo for many worthwhile services rendered to the main Parish church. Dr Gabriele, who had done his own studies at the University of Naples, wished his sons to receive similar educations at the best overseas schools.

And in 1792, having decided to send the eldest son, Filippo, to complete his theological studies in Rome, he took advantage of this favourable opportunity to send along with him the younger son Arcangelo; the latter having spent some years in the Episcopal Seminary of Malta, studying Italian humanities, went together to study Latin humanities at the Collegio Romano (2).

With the disbanding of the Order of Jesuits in 1772, the famous Collegio Romano did not remain suppressed. The Pontiffs were always prepared not only to create new institutions, but moreover to preserve those which from ancient origins continued to produce benefit, all the management, given to maintain that noble university, established in the sixteenth century, during the time of the patriarch Ignatius, from the same saint Duke of Candia Francesco Borgia, and by later works of the most learned fathers, taken step by step to the highest level in the range of studies and in teaching methods.

With the Jesuits suppressed, the college promptly survived with first grade secular priests. With many of the Jesuits having been secularised, they could maintain more easily than others the spirit of the premier institution.

At the Collegio Romano the young Arcangelo ably distinguished himself as much by his conduct as by his study. Various certificates he received, especially between 1794 and 1796, fully witness his deep modesty and his excellency in written latin, in prose as well as poetry. The humanities professor Don Domenico Argentini often ranked him first among all the students in writing, praising him for the style he used, then bestowing the distinctions of princeps principum in prose discourse, and princeps sanatus in metric discourse.

In the meantime, the wars which overran all of Europe at that time, led by General Bonaparte, forced the father of the two Pullicino brothers (the elder of whom had completed his theological studies under Arbusti (3) and was already ordained priest, while the younger had finished his literary studies) to summon them back to Malta. They returned just in time, before the French fleet, headed for Egypt, had occupied the island in June 1798. Returning to Malta in October of the previous year, they had encountered such a vigorous tempest at sea that they almost perished. However, such were the conditions that they were forced to call in at each coastal town of Calabria and Sicily.

The young Arcangelo did not remain idle during the blockade of Valletta, which the French kept up against the population of the Maltese countryside, who would not tolerate the yoke of a regime so hostile to religion to which the Maltese were, as they are to this day, strongly attached. Following the example of his brother, the new priest Don Filippo, he set about in this critical situation to help those sick with fever, who had been sent from the field to the hospital of San Giuseppe in Zebbug, and for a full two years he kept continuously practising the studies he had already done, and which had brought him such great distinction in Rome.

When the blockade was over and the islands of Malta were entrusted to the protection of Great Britain, who through its naval power provided a secure pledge of total and lasting peace, Dr Gabriele Pullicino being fully cognisant of the many benefits of a good and completed education in a great and recognised University sent back his son Arcangelo, who wished to follow his father’s profession, to take up a course of medical studies at the ancient and celebrated School of Naples.

There, he had the good fortune to have as teachers the learned professors Sementini (4) for chemistry, Cutugno (5) for anatomy, and Andria (6) for practical medicine. Of these, the last had formed an extraordinary affection toward his pupil Arcangelo, in whom he admired not only the love for study, but above all his good manners and his modesty. He frequently preferred to have Arcangelo at his side rather than others to assist him in his visits to his patients.

It’s impossible to measure how greatly young Pullicino profited from the tutelage of such proficient teachers: as was certified so many times by the same Professor Andria, as well as by several of his fellow disciples; above all by the doctor Vincenzo Lanza (7), who himself became, with the passage of time, professor of practical medicine in the same University of Naples, and who rose to great renown in the Court of the realm; they never forgot their young colleague for whom their teacher had shown a special affection.

Having finished the whole course of study, the young Pullicino graduated and received his doctoral degree at Salerno; as this was the most sought after, and the most respected, it was conferred at the oldest centre of the old and famous medical school of Naples.

In those days, there were many Maltese who aspired to do their medical studies at Naples; and those with more or less success managed to obtain their doctoral degree at Salerno: in contrast with others of slightly earlier days, who seemed to prefer the more renowned School of Montpellier. Not that there were no Schools of medicine in Malta in those days. Before the fall of their order in 1798, the Knights of Jerusalem, who had set up and managed their own hospitals, had opened a special School of Medicine and Surgery in the same establishments. However as this was limited in a small country where practice was restricted to the observation of the few cases presented in the island, the School was not able to foster substantial study. The art of medicine, derived largely by practical study, is widened to the extent that it is based on broad and varied observation. So it was that the Maltese, when they wished to pursue the medical arts, more than the mere love of science, flocked to Montpellier or to Naples.

There probably was much encouragement to do so, heeding the wise advice and good works of many of the Knights: who although foreigners to the island, were nevertheless strongly bound to it, since they had to lodge their riches there, and to spend their days there, nobly aspiring to improve in every way the conditions of the population among whom they had to govern.

When under Grandmaster de Rohan the French Knights had prevalence in the affairs of the island, with their advice they encouraged the young Maltese to study medicine at Montpellier. However when the Order went into decline and then fell, the same Maltese, already used to completing their studies overseas, turned to a country which was closer, and where medical study was of equal renown. Around the year 1800, the University of Naples became the School from which Malta welcomed worthy doctors, not the least distinguished of whom was Dr Pullicino.

Chapter 3: A Healing Hand Amidst Pestilence

He returned to the country of his birth in 1807, and to the family home, from where for several years he practised his medical profession among the residents of Zebbug. He regularly spent time in Città Valletta, where his brother Don Filippo, back from Naples, was now Professor of Canon Law at the University. This frequenting of the island’s capital provided him with the opportunity to commune with men of learning, and so the motive to not neglect the exercise of letters, particularly Latin, the study of which he kept up with the same ardour he had shown when he was still a student in the Collegio Romano.

In the practice of medicine he found that study deepened understanding of the art more than practice. When making visits to the sick he developed the habit of gathering the observations which it was necessary to do, and accurately making notes in such a way that reached the stage of setting down some important works relative to the art.

Meanwhile a fierce plague had broken out in Malta in 1813. It was the latest in a series of terrible diseases to which at various times the islands of Malta were subjected: but it was one of the more serious type. The village of Zebbug was to suffer particularly badly. During this mournful occurrence Dr Pullicino applied himself with great courage and selflessness to the care of the plague victims of that district. In accordance with the prevailing opinion he declared unreservedly that the plague was the externally contagious type, requiring those affected to be separated from their families, and with great self-sacrifice and mortal danger he went everywhere to provide relief to all who needed his skills. It was at his instigation and through his great efforts that the government, seeing contagion spreading further, decided to erect wooden barracks outside the Casal, in the district called Sant’Andrea, where all the plague-ridden were put into confinement. This expedient was the means by which they succeeded in staving off disaster, and from then on the plague began to wane, and soon disappear altogether from that village.

The plague ended in October 1813, and Dr Pullicino began to compile the many observations that he had been given concerning that memorable epidemic. Of these the most significant accounts which remain are a detailed report written many years later by Baron Depiro (8), and a report written by an English physician, Mr. Brunell.

However it was Dr Pullicino, who had played a very active part in this calamitous event who was perhaps the very first to propose that a history of this epidemic be produced: materials were collected, the work was nearly done; however, it was entrusted to a to friend, or someone he thought he could trust, to be read, but after a great deal of lost time, it could not be retrieved for publication.

In August 1814, Dr Pullicino meanwhile chose to marry Signorina Marianna Schembri, a young woman with many noble qualities, born in 1793, daughter of Dr. Giovanni Schembri, Royal Judge of the courts of Notabile, and afterwards Assessore for Archbishop Mattei. Among the many qualities that distinguished the young bride not the least to shine was her great skill in music. The only pupil of the famous Maestro Francesco Azzopardi (9) she played the piano with extraordinary skill. She had no equal in the country. Expression, strength, precision, and agility were particular qualities for which her sound received highest admiration. The same Maestro Azzopardi, educated in Naples, admired her so much that it was she alone to whom he ever agreed to give music lessons, and when he died she was the sole heir of all his works of secular music. As well as for such musical virtues, the young Schembri also distinguished herself greatly for her rare modesty, good manners, and piety.

From this union came many children and Dr Pullicino took particular care, educating them himself, rather than leaving it to others. His many sources of income allowed him to live comfortably, and left him free to give up the practice of medicine to apply himself to the ongoing education of his children.

He only carried on his medical practice in order to provide free treatment to poor people, particularly where he used to spend his summer holidays and was besieged by poor patients who needed his care. But his predominant thought was the proper education of the children.

Perhaps it is not always considered wise for a good parent to devote all possible effort to raise and educate well under his own eyes his children from childhood. Secondary education, more important than primary, can not have a better guiding hand than that of the parent. Who can appreciate its value, or devise its methods better than a parent? Left to the hands of others it often happens that it deviates from the straight path. It is true that not all parents can do this, especially when they themselves lack sufficient education. But when they can and do, immense benefits can be derived from this sacrifice.

On the other hand, Dr Pullicino in this undertaking showed great concern from the beginning to see that the children were raised in the practice of sound and rigorous morality. Religion was the central focus of all his actions. He could therefore spare nothing in the education of the children. For him, intellectual, moral and religious education, were three aspects of human development, which ought never be divided, but always closely joined together, in equal measure and mutual proportions.

Then to complete this task of education, he further arranged that after their studies at the university faculty, the children were to visit foreign countries for a considerable time, and so their youthful studies were rounded off with discussions and lessons of various types, with which the most distinguished foreign professors are wont to grace major Universities.

He knew well, through his own experience, how conducive it is to travel the world, especially with the aim of educating oneself, not as much with still inexperienced adolescents, as with young men, who do regular studies can better appreciate higher knowledge, taught by substantial and men in science and letters, in large and renowned university.

Meanwhile in this considerable amount of time Dr Pullicino continued assiduously to practice by himself in the study of literature, especially Latin, which he greatly cherished. He took part in several literary academies, which emerged at that time either open to the public, or in circles of extensive number of friends. The love of letters was at that time very much alive among the Maltese. Even stronger were the traditions of the distinguished college which the Jesuits had run in Malta in the time of the Knights, and whose last representative was still living, old and blind, the renowned translator of Catullus, the abbot Rigord. (10)

In these academies people were invited to recite their compositions in the manner of the best literary cultivators; large numbers used to participate in these activities; and often among these was Dr Pullicino; of his compositions the latin ones were appreciated most of all, for their insights, the facility of the verses and the purity of the language. Exceptionally beautiful were those written in commemoration of the passion of the Redeemer.

Meanwhile at the turn of 1831, Dr Pullicino came to suffer a serious loss with the unexpected death of his wife. After a short illness, with all the medical efforts proving useless, she yielded her spirit to the Lord on Good Friday, the first of April of the said year. The death of someone so cultured and distinguished by virtue was a very serious loss, almost a sudden halving of a family, of which she was a great ornament and a most valuable support. Dr Pullicino sustained such a loss with indescribable resignation and acceptance of divine will. The mortal remains of the deceased were buried in the noble tomb in the church of St. Paul in Valletta.

The distress caused by the death of his wife was made worse a year later by that of his brother Don Filippo, who having become subject to severe sadness was finally seized by apoplexy, from which he suddenly died on the evening of July 31, 1832 (11). His body was borne to and buried in the choir of the Church of Zebbug. He was priest of blameless morals. Affectionate not only to his own but also to the very many young people who studied under his direction. He was bitterly mourned by all, and his memory was honored by his students with a solemn funeral in the church of Jesus.

Around this time the country had begun to shake off the long torpor into which they had been driven by the great distress they had suffered during two years of the blockade of Valletta. Many felt the need to wake up into a better political life. The British for more than thirty years had ruled the islands of Malta in order not to alter suddenly the political constitution of the country. All public works were administered with the help of private advisors to the military government.

Chapter 4: Politics and reform

Many municipal corporations either from the desire to centralize public affairs, or from having been rendered almost useless were methodically abolished. In this way a large number of intelligent and well-intentioned Maltese finally felt impelled to act, and to petition the King for some new political concessions for the good of the islands. In this group we find Dr Pullicino. The effect of these first steps was to gain no more than a small governing council, composed of some citizens elected by the government, which could not initiate the adoption of governmental measures, and was called only to give their opinion about matters which the Head of Government might wish to subject to their consideration.

This concession failed to satisfy the desire for more, many shortly after advised to once again seek a Parliament. At the head of this movement, we find Dr Pullicino, Camillo de Baroni Sciberras, and the businessman Giovanni Battista Vella. Together they wielded no small influence, and attracted others. These gradually increased to a large number to form a National Committee. They sent agents to London. They got to represent their interests in Parliament a character who defended them selflessly, this was Mr. W. Ewart. (12)

There was no shortage of difficulties to discourage him in this undertaking. But he held his ground: and the firmness of Dr Pullicino and his two companions yielded excellent results for their country. A petition signed by a large number of citizens was lodged in the House of Commons, and this led the Colonial Secretary to send to Malta a Commission of Inquiry, to give an exact account of the grievances being alleged, and the reforms being sought. In this enquiry, entrusted to two distinguished persons, Mr Austin (13) a learned Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of London, and Mr Cornwell Lewis (14), an expert statesman, who would later ascend to the highest levels in Britannic diplomacy, Austin has the most skilled came to take the more prominent part, and it is to him that we are indebted for the greater part of the reforms he proposed and for the most part put in train. Dr Pullicino kept a close relationship with these commissioners, and especially with Mr Austin, whose knowledge, probity, justice and impartiality he greatly admired. This enquiry, opposed by some of the impetuous and suspicious patriots, but assisted by the moderates, led by Dr Pullicino, brought about the introduction of excellent radical reform which was to entirely change the political aspect of the country.

And it was following this Inquiry that freedom of the press was granted under certain laws, that many of the chief positions which had previously been inaccessible were entrusted to the Maltese, that taxes were reduced on some items of general consumption, that a system of public education was initiated, and freedom of commerce was put on a better basis. Many other reforms besides these would have been set up, if in 1837 cholera, spreading in the country for the first time and not thrown all the population into great consternation, and a change in the British Ministry had not interrupted the course of the Commission’s work.

Meanwhile in August of this year, Dr Pullicino was to suffer another great distress, yet one which he would bear with unspeakable resignation. This was the death of Maria his last surviving and eldest sister; she had withdrawn with him to Mqabba, to escape the raging disease that infected the whole island, and at the age of around sixty-six years she died of this disease, and was buried in the ancient church of San Basilio. She was a woman of holy life. She was unmarried and lived a secluded life. She treated the poor with great charity, spending a great deal of her time making clothes, which she anonymously distributed among those with greatest need. Zebbug would experience a great loss from her unexpected.

In spite of all this Dr Pullicino did not relent in his studies. Rather, during this period they took a rather different direction. The active role he played in the affairs of his country gave him the opportunity to occupy himself with particular attention in the study of political science. He wished to deepen his understanding, not with the changeability of a demagogue, but with the reflection of a sincere reformer. In these studies he always kept sight of the great principle of every healthy politic, that is religion. With this in mind, he began a review of the constitutions and affairs of various countries on the earth, and particularly those of Europe, as appears from the many annotations he wrote in the course of these, his studies.

His satisfaction was great, when he saw given to the island of Malta (something greatly longed for by the good people) a civil Governor, and for the first time a Catholic, in the person of Mr R. More O’Ferrall. This happened in 1847. Mr R. More O’Ferrall (15), a person of extraordinary administrative ability, undertook soon after his arrival in Malta radical reforms in various departments of the island. Like Mr Austin in 1837, who had laid out the fundamentals of reform in the country’s constitution, Mr R. More O’Ferrall attended to the extension and implementation this new model. The qualities of being a Catholic, which distinguished, then served to attenuate and remove restrictions which had been formally inspired by Protestantism and which weighed heavily on the Catholic population of the country. All this revived the spirit of Doctor Pullicino, who saw this in great part is a vindication of the things he had undertaken to improve the conditions of his country. and this prompted him tosearch for more ways to bring reform forward. He was at this time in very close relationship with Doctor Bowring, the greatly renowned statesman, and a very active and influential member of the British Parliament. Doctor Pullicino, with the assistance of several friends, and the agency of Dr Bowring (16), brought the state of the island once more under the consideration of Parliament. The political circumstances in Europe were favourable. Mr More O’Ferrall did not oppose, and in fact supported the movement. And this resulted in the end, in the obtaining of the Council of Government, composed of eighteen members, half of whom were elected by the people. However, this institution seemed imperfect to some, but Dr Pullicino was pleased to see in it a form of constitution that was more extensive and free, that he hoped the country would obtain with time.

In the first selection of elected members of this Council, Dr Pullicino was elected with a great number of votes. And during the first five year session, he worked hard to promote measures useful to the country, and to defeat others prejudicial to it. He was accompanied in this assembly some good citizens who would co-operate with him in advancing the well-being of the island. They worked together with zeal to support the article. In the compilation of the criminal code, which he cleared the Catholic religion as dominant in the island of Malta. Almost single-handedly, but with little success, he supported the law which required criminals to remain in their homes at night time. He fought strongly against the law of compulsory military service, and persuaded Governor Reid (17) to adopt instead to measure of simple voluntary service. He was very useful in the special committees of this Council, when he gave the greatest priority to investigate the Department of public works, and when he sought to introduce gas lighting to Valletta.

In the second five yearly election, he would have been re-elected, if a great number of votes had not been divided between him and other members of his family. This happened at the end of 1855. At this time. He then retired completely from public life, attending exclusively to his private life, spending all his time in study and prayer.

It would be remiss to fail to note that both Governor More O’Ferrall, and Governor Sir W Reid, who got to know him during his service in Council, had held him in high regard. Sir W. Reid was a person of proverbial probity; and as such he greatly admired the honesty and simple manners that he had. It was from him that he often sought advice, particularly in those things which pertained to the operation of the Council. Two such similar characters could not help but empathise with each other: and it was this empathy that gave rise to so much trust in each other.

Chapter 5: Sunset years

Meanwhile in the summer of 1851, Dr Pullicino and part of his family visited Rome, the city where he had undertaken his first studies, and where, especially he had become attracted to the intense love that he professed for the Catholic religion. This trip provided the occasion to see Firenze for the first time, and to admire the exquisite works of art which are housed there, and to see the city of Naples again, which reminded him of his former teachers and colleagues with whom he had studied the arts and medical science.

In 1854 Dr Pullicino had already reached the age of seventy-three; and although of very strong constitution, feeling, however, that he was getting closer and closer to the end of his life, he wished no more to think of other things apart from domestic life, and a better life elsewhere to which he always tirelessly aspired.

Simple was the way in which he generally conducted himself in his domestic life. Rising in the morning he attended mass with great devotion, held in the private Chapel of his house. He did this even to the end of his illness, and until shortly before his death. Afterwards he would attend to his domestic affairs, all of which he looked after himself until the very end.

He would then take himself to church, on most occasions to the Carmelites, where he remained for a long time in adoration of the holy sacrament. After lunch, a light meal which he took at home at midday, he did not lie down; he found greater recreation in the cultivation of plants, moving at a slow pace, at times taking seated rests.

Then he spent much of the afternoon in reading and study. Towards evening he took part in the exercise of the way of the cross in the church of Santa Maria di Gesù from there he passed to the church of San Paolo to to remain up to the power set aside at night to the adoration of the sacrament. He never indulged in conversation; for him each day’s evening conversation for more than an hour was with Jesus of the sacrament.

In church he remained kneeling never seated. And he maintained this practice right up to the end of his life. This gave rise to great wonder in everybody to see him all the days for many hours in such a position, without moving once towards the sacrament. At supper he would only take a very small meal, most times some drink, and nothing on fast days. After supper. He returned to his reading, and then to say prayers; he would never go to bed until after midnight. He often fasted: on the days of obligatory fast he took nothing but strictly Lenten food. He passed each Lent with meals seasoned only with oil. On fast days he would only eat once a day.

Although he was a man of rather lively temperament, he always seemed very patient, undergoing any sort of adversity in silence; and he was each day more wise in all the public and private difficulties that he encountered. The love he bought his children was great, and he made whatever sacrifices he needed to raise them well, and to leave them well provided for. Towards the poor he was full of charity, and he supported them with many ongoing alms. In a word, he was a perfect Christian and the best of fathers, who, while always thinking of his own, did not omit at the same time to make use of the many gifts received from God by sharing it all with some charity.

Concerning this charity, here I have to add that it was as generous as it was secret and made with discernment. Almost no one knew what he gave to the poor, not even the people in the household. He used such discretion to help the needy, far more than with alms, he aided those that did not have the means to work. So it was that he gave special help to the tenants of his lands, either by letting such lands at low rents, or by allowing that the payments that they made were suitable to them. He rarely, if ever, increased the rents on his possessions. Then he almost never took anyone to court to recover his debts.

Central to the manner of thinking of Dr Pullicino, and worth noting, were his very healthy and firmly held principles. He was not a man who bent and adapted himself to circumstance; but honesty, rectitude, conscience, religion, and candour were his constant guides. He only accepted politics based on justice and honesty. At heart. He was conservative, but did not exclude that true liberty which opposes abuse and favours true progress. So it was that he detested the overrunning of Europe and of Italy in particular, because it was based on the usurpation of the rights of the Church. He considered friendship as a very rare thing, did not have familiarity with many, although he showed respect to many, and goodwill to all. He did not make a distinction between poor and rich; he showed everybody the same treatment, according to their required needs. In fact, if he exercised partiality it was in favour of the poor, to compensate them for the many disadvantages [angarie] that come from the flattery that some extended towards the rich. Religion was for him the supreme remedy. Anything which distracted him from religion, he regarded with suspicion. He considered the education of children as very difficult, for which reason he did not encourage marriage for those who were not naturally impelled towards it.

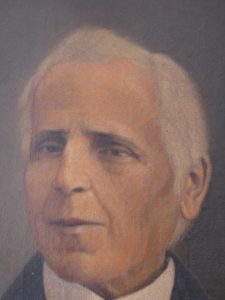

Of the devotions he considered that of the most Holy Sacrament the highest; and he had a special and tender attachment to the Virgin Mary; in addition to this last devotion, he considered that of the patriarch St Joseph as of the highest merit. He abhorred luxury, as something opposed to the modesty which he greatly preferred. He was a man of simple manners. He did not seek or aspired to honours or distinctions. He was always grateful to God for the good fortune with which he had been provided, although he appreciated the gifts of the spirit above everything else. He had great confidence in divine providence; moved by various circumstances in which God had unexpectedly provided much help and gifts. He professed a particular devotion to St Paul, since he recognised that the greatest good of the islands of Malta, faith, had come from his protection. His example was the most perfect: his children and his acquaintances could never say that they had seen things of him or heard words, which were anything but edifying. He taught by his actions, more than by his words. Of rather short stature, and somewhat thin girth, he wore an expression on his face of such goodness, and kindness, and at the same time of steadiness and seriousness which attracted everybody, except the sad, and those who tremble whenever they encounter someone whose demeanor can stop them on the path of their wrongdoing.

Chapter 6: Embracing eternity

But here, when Dr Pullicino had completed his eighty-first year on 5 October 1861, his health, which had already for some time shown some decline, began to show clear signs of decay. Nevertheless, he continued to pray at home, never wishing with all this to diminish the customary rigour of his way of life. So it was that in December of the same year he began to be troubled by a strong dysentery; this gave him some fear. Around the twentieth of the month, the illness forced him to subject himself to a more regular medical regime. At the infirmity continued to make advances; so that on Sunday the twenty-second of the same month, it was not possible to take him to the sermon of the fourth Sunday of Advent in the church of St John, where Padre Vera, a Dominican, preached, and where he was always used to attend the sermons which he gave there throughout the year. Christmas Day was the last day in which he was able to leave the house to hear holy Mass, and to attend in the afternoon exercises of piety.

On the twenty-seventh of the month, having changed his treatment on the advice of very experienced doctors, the illness seemed to show some signs of retreating; but returned after two days with the same force as before. Meanwhile, he was not able to leave his house, but he did not fail to drag himself to the private Chapel of his own house to hear holy Mass and recite many other prayers during the course of the day. On the thirty-first, although his strength was very weak he wished to go to chapel, and was barely able to attend for the last time at the bloodless sacrifice.

As on the following day, the first of the new year 1862, the loss of blood increased, and at the same time the weakness, he knew that it would be very difficult to survive; and then he himself urged his children to arrange for the Holy Sacraments, if he seemed in danger of death. In the hours of the afternoon therefore, a little after sunset, the Rector of San Domenico brought the Holy Viaticum; he wish to receive this kneeling on the ground, supported by his children. Receiving the Holy Sacrament gave him great comfort.

A strong and frequent hiccup began in the morning, causing him trouble: and from this symptom he knew well that death was very close. This hiccup stopped before the Viaticum, and returned some time later, continuing for almost all the following day, Thursday, 2 January, so the illness grew worse. Towards evening, around 10 o’clock at night it took a very alarming turn. And so it was, towards two hours after midnight, that he came to receive extreme unction, and the indulgences that in such circumstances the Church accords the faithful, and which he received with great attention and fervent devotion.

With the greatest serenity of mind, and with a very placid spirit, he began to reason with his children, who stood around weeping inside; and giving them with extraordinary lucidity of expression, a clear description of his malady, saying that some infirmities, without giving any exterior sign, take hold in some internal organs, and has now remain undetectable up to the end, but suddenly manifest themselves and become fatal.

He then proceeded to commend his soul to God with great affection and compunction of spirit; and from his mouth came the repeated sounds of beautiful prayer which he recited with great clarity and affection, and with which he seemed that he would go to his death prepared. He was not a dying man begging for help from bystanders, but a loving father who on his deathbed gave to his children, after so many others, one final lesson – how to die well.

Meanwhile, on the morning of Friday, January 3, his illness seemed to want to make a truce. After eight in the morning there was a great change for the better, which gave great hope to his eager family so anxious to see him return to life; however, this was no more than the improvement which foretells of the final crisis, which precedes death. Some time after three in the afternoon the illness took on a still more alarming aspect. Without losing any use of his senses, he began to feel such yearnings that he did not believe that he was in his own bed, but in a place from which he could fall. This anxiety bitterly tormented him for the whole of the following night, although he bore it with unspeakable patience.

Towards the end of Saturday morning January 4, he began to feel less anguish, and also began to lose his senses. The first was his sense of sight. He was no longer able to see the light of the new day, which dawned; and because his children, great distress to see him feeling about with his hands seeking some object which was under his very eyes, but which he could no longer see. Being aware by then, of the progress of the illness, and lacking any force any longer, he composed himself in the attitude of a dying man waiting for death. If he was given a word of spiritual comfort, he would immediately recite a psalm or short prayer. If he was offered some refreshment, he would thank the one who brought it with a sweet smile, instead of receiving from them. The gratitude owed to him because all he had done in his life for them. . To see him in that position, is radiant face turned to heaven, and with the sweetest words always on his lips, he appeared to recognise a distant image of the dying patriarch St Joseph to whom he was most devoted.

Towards 9 o’clock the illness seemed to become more rapidly worse, so that at half past ten, sweetly and without any sign of distress, he passed to the peace of the Lord, and his beautiful soul flew to the bosom of God. . So was the death of a man who spent his long entire life in constant struggle to improve himself, to help his fellow beings, and to serve God; he died as holy as had been the life he now completed. . I add nothing else. I end this notizie, which, though brief, I believe, will be sufficient to pay honour to a man adorned with virtues that are nowadays very rare, and to give encouragement to those who wish to follow the same path.

Translator’s footnotes

1

[p.6] Limosina has now largely been supplanted by the “learned” form elemosina meaning `alms’.

2

[p.7] The Collegio Romano (Roman College) was founded in 1551 by Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), as a “School of Grammar, Humanity, and Christian Doctrine”. In 1773, following the suppression of the Society of Jesus, the university was given over to diocesan clergy of Rome. It reverted to the Jesuits on 17 May 1824 by Pope Leo XII, after the restitution of their order.

3

[p.8] Agostino Arbusti was professor of dogmatic theology at the Pontifical University. He died in 1795. He was author of Tractatus De Cultu Sanctorum Reliquarum ac S.m. Imaginus., and wrote a Short Life of St. Anthony of Padua.

4

[p.9] Dr Antonio Sementini (1743 – 1814) was an eminent doctor, a native of the City of Mondragone who, because of his important studies, was counted among the most famous scientists of the time. His field of research ranged from vital physics to the study of anatomy and disease classification, distinguishing himself as a forerunner of the studies of neurology and psychiatry.Because of his skills, he enjoyed great esteem and respect throughout the Kingdom of Naples and, although known as a supporter of libertarian ideas, he managed to survive the fatal punishments that King Ferdinand IV of Bourbon reserved towards those who had shared the ideals of the Neapolitan revolution of 1799.

5

[p.9] Dr Domenico Cotugno (1736-1822) was an Italian physician, born January 29, 1736. He studied medicine at the University of Naples from 1753. Poverty and illness plagued him during his training. After barely surviving a critical illness that he contracted while resident physician at the Neapolitan Hospital for Incurables, he received his doctorate in philosophy and physic in 1755, at the age of 20, and became an assistant at the Ospedale degli Incurabili. In 1761 he became professor of surgery at that hospital and continued his investigations. He was subsequently for 30 years professor of anatomy at the high school of Napoli as well as director of the Ospedale degli Incurabili. In 1808 he was appointed archiater (Royal Physician). He ceased lecturing in 1814, suffered a cerebral embolism in 1818 that recurred in 1822, and to which he succumbed.

6

[p.9] Nicola Francesco Maria Andria (d’Andria) (1747 – 1814) was an Italian physician and philosopher. He was born in Andria (modern Taranto). He studied law in Naples, publishing in 1769 a Discourse on political servitude. Although a graduate in law, he had an inclination for science and this prevailed, so that after a short legal practice, he devoted himself to the study of medicine and chemistry. Cotugno was his teacher for anatomy, while in chemical studies he benefitted from the teaching of Vairo. He studied clinical medicine at the hospital of the Incurables in Naples, and still only twentythree years old, Cotugno encouraged him to open a private school where, as well as medicine, he taught chemistry and experimental philosophy. In 1775, he held the temporary chair of practical medicine at the university of Naples. In 1777, he was appointed to the permanent chair of agriculture, as in the meantime he anonymously published Lettera sull’aria fissa (Naples 1776), recognized by many as his work. His work as a professor was mainly research and teaching at the University, where he gave various lessons from natural history, theoretical medicine and practical agriculture, and published several works for use by medical students in various parts of Europe. In 1808 he began to dictate lessons of theoretical medicine, and in 1811, of pathology and classification of disease. Sick and now blind, he was discharged in early 1814 , awarded the title of Knight by Joachim Murat (brother of Napoleon ), and December 9 died of typhus in Naples, where he was buried in the church of Santa Sofia , together with his colleague Antonio Sementini. Three years after his death his name appeared in the biography of the illustrious men of the Kingdom of Naples by Gennaro Terracina.

7

[p.9] Dr Vincenzo Lanza (1784 – 1860) was an Italian physician, politician and professor. In 1800 he moved to Naples, where he studied medicine. Upon graduation in 1814, also in Naples, he was appointed professor at the medical clinic of the Ospedale degli Incurabili and the following year the director of the medical clinic in the Ospedale della Pace. In 1831 he was made professor of the chair of practical medicine of the University of Naples. On 18 April 1848 he was elected Member of Parliament of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and appointed vice president of the Chamber of Deputies. He was a liberal politician and supporter of the constitution granted by the king. After the anti Bourbon riots of 1848, Ferdinand II dissolved parliament, and began to persecute its liberal members and chasing real and perceived revolutionaries. The reactionary and anti-liberal repression of the sovereign also threatened Lanza, who was forced to abandon the city to avoid his capture. In 1849 he settled in Genoa where he continued to practice his profession as a doctor. In the years of his Ligurian exile, the trial was held in Naples against the Liberals and Lanza was sentenced to death. Only later, in 1856, did Ferdinand II revoke the judgment against Lanza, giving him permission to re-enter the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies so he could be reunited with his family and continued to pursue his medical profession. He died on April 3, 1860 due to apoplexy.

8

[p.12] Ragguaglio Storico della Pestilenza che Afflisse le Isole di Malta e Gozo negli Anni 1813 e 1814 – Barone G.M. De Piro Livorno 1833.

9

[p.13] Francesco Azzopardi (Notabile, May 5 1748 – Rabat, February 1809) was a Maltese composer and music theorist. He received his musical training in Malta and during his stay from 1763 to 1774 in Naples at the Conservatory of San Onofrio under Carlo Cotumacci and Joseph Doll. He worked at St. Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina, and, from 1789 following the Napoleonic invasion and flight of the Knights of St. John, combined his responsibilities at Mdina with those at St. John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta. One of his successes was a setting of Metastasio’s libretto La Passione di Gesù Cristo he conducted at the Manoel Theatre in Valletta in 1782. He is known especially through his work Il Musico Prattico, which appeared in French translation by Nicolas-Étienne Framéry.

10

[p.15] Louis Maria Rigord was born in Malta May 4, 1739, and died in 1823. At the age of fifteen he went to Palermo to enter the Society of Jesus, and was educated at the Jesuits College. On the expulsion of the Jesuits from Sicily in 1767 he went to Rome. He translated Catullus into Italian, and wrote several pieces of poetry, both in Italian and Maltese. He wrote a good number of sonnets, madrigals, canzoni, elegies and epigrams under the assumed name of Ruidarpe Etolio. He was held in high regard by everybody, including the two very distinguished writers, the Englishman Hookham Frere (1769 – 1846), and the Italian émigré Gabriele Rossetti (1783 – 1854).

11

[p.16] Don Filippo Pullicino (21 November 1762 – 31 July 1832) was ordained priest in Rome at San Giovanni Laterano on 24 September 1796 by Cardinal Della Somaglia. He was Professor of Canon Law at Malta University. While in this work Paolo describes his uncle as having become subject to severe sadness was finally seized by apoplexy, from which he suddenly died, he gives a different account in his Libro di Notizie riguardanti la Famiglia Pullicino Schembri where he writes that Filippo died towards evening tragically swimming at Pieta’. In his Libro di Notizie della Famiglia Pullicino Paolo’s brother Antonio records that Filippo died bathing at Msida, having been found drowned.

12

[p.18] William Ewart (1798 -1869) was a British politician. He was an advanced liberal in politics, responsible during his long political career for many useful measures, including the abolition of hanging in chains, the abolition of capital punishment for cattle-stealing and other offences, and the establishment of free municipal libraries.

13

[p.18] John Austin (1790 – 1859) a noted British jurist who published extensively concerning the philosophy of law and jurisprudence. Austin served with the British Army in Sicily and Malta, but sold his officer’s commission to study law. He became a member of the Bar during 1818. He discontinued his law practice soon after, devoted himself to the study of law as a science, and became Professor of Jurisprudence in the University of London (now University College London) 1826-33. Thereafter he served on various Royal Commissions, including this one.

14

[p.18] Sir George Cornewall Lewis, (1806 – 1863) was a British statesman and man of letters. In 1833 he undertook his first public work as one of the commissioners to inquire into the condition of the poor Irish residents in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. In 1836, at the request of Charles Grant, 1st Baron Glenelg, he accompanied John Austin to Malta, where they spent nearly two years reporting on the condition of the island and framing a new code of laws. One leading object of both commissioners was to associate the Maltese in the responsible government of the island.

15

[p.20] Richard More O’Ferrall, (1797-1880), governor of Malta, was eldest son of Ambrose O’Ferrall by his first wife, Anne. From an early age he joined in the struggle in Ireland for civil and religious liberty. Unlike his brother John Lewis More, he declined, as a conscientious catholic, to enter the protestant university of Dublin. After the Catholic Relief Bill passed in 1828, he became in 1831 the Member of Parliament for Kildare, his native county, which he represented without interruption for seventeen years (1830 -46), and afterwards for six years (1859 -65). In 1835, under the Melbourne administration, O’Ferrall became a lord of the treasury; in 1839 secretary to the admiralty, and in 1841 secretary to the treasury. In 1847 he severed his connection with Kildare to assume the governorship of Malta. In 1847 he was made a privy councillor. He resigned the governorship of Malta in 1851, declining to serve under Lord John Russell, the prime minister, who in that year carried into law the Ecclesiastical Titles Bill, in opposition to the papal bull which created a catholic hierarchy in England. O’Ferrall died at Kingstown, near Dublin, at the age of eighty-three, on 27 Oct. 1880. He had been a magistrate, grand juror, and deputy-lieutenant for his native county and at his death was the oldest member of the Irish Privy Council. He married, on 28 Sept. 1839, Matilda (d. l882), second daughter of Thomas Anthony, third viscount Southwell, K.P. By her he left a son, Ambrose, and a daughter, Maria Anne.

16

[p.21] Sir John Bowring (1792 – 1872) was an English political economist, traveller, miscellaneous writer, polyglot, and the 4th Governor of Hong Kong. Bowring ranked with Giuseppe Caspar Mezzofanti and Hans Conon von der Gabelentz among the world’s greatest hyperpolyglots – his talent enabling him at last to say that he knew 200 languages, and could speak 100. His chief literary work was the translation of the folk-songs of most European nations, although he also wrote original poems and hymns, as well as works on political and economic subjects.

17

[p.22] Major-General Sir William Reid KCB (1791 -1858) was a British soldier, administrator and meteorologist. Born at Kinglassie, Fife and educated at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, Reid was commissioned lieutenant of engineers in 1809, and in 1810 joined Wellington’s army at Lisbon. In 1815 he participated in Sir Edward Pakenham’s unsuccessful attack on New Orleans and in 1835 commanded a brigade in the British Legion raised by the Queen Regent of Spain. Subsequently Reid served as Governor of the Bermudas (1839 -1846), of the British Windward Islands (1846 -1848), and of Malta (1851 -1858). He was knighted in 1851 and promoted to major general five years later.

Reid had been sent to the Leeward Islands in 1831 to direct the task of reconstruction after the Great Barbados hurricane in which some 1,500 people perished. During his two-and-a-half-year stay he became absorbed in trying to understand the nature of North Atlantic hurricanes, which led to a lifelong study of tropical storms. He published An Attempt to Develop the Law of Storms by Means of Facts (1838) and The Progress of the Development of the Law of Storms and of the Variable Winds (1849).