Paul Pullicino (ta’ Tony), a transcriber of the diaries, gives excellent context in his preamble to these primary source texts. This post adds to that from a broader historical perspective.

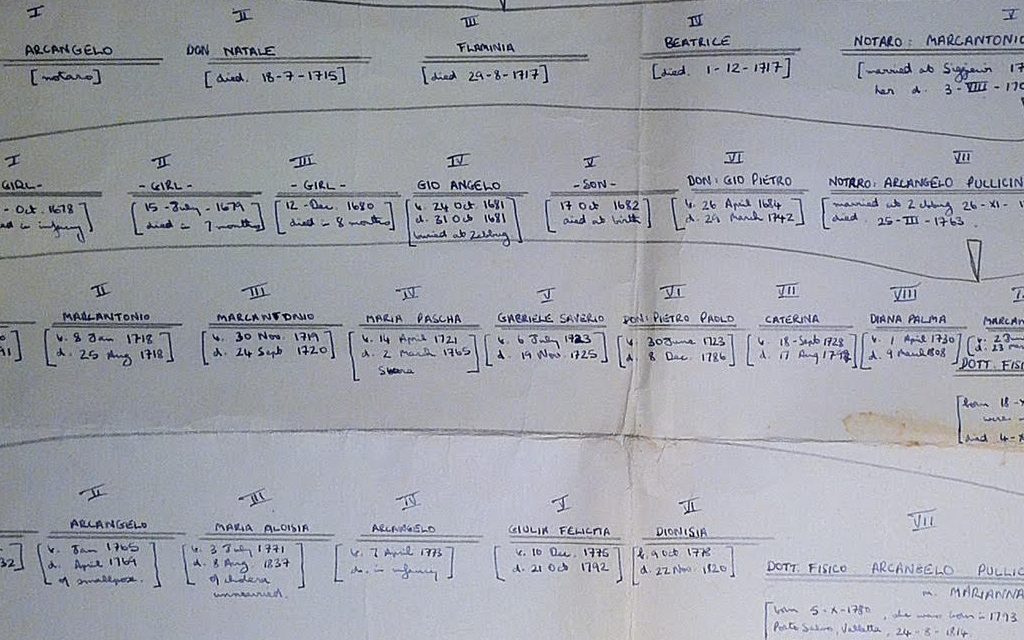

I first encountered the family tree in a format similar to the one below, which my father was working on when I was around 10 years old.

Paul’s transcription of the diaries, performed when he was 18 years old, allowed them to eventually be published electronically by his brother John Pullicino many years later. The electronic publication was important in alerting the broader family to the importance of these records.

Initially I was only aware of my father and uncle’s contribution. However, their commendable work stands on the shoulders of others. Various members of our family throughout the last 300 years have dutifully safeguarded the diaries, transcribing older entries, traversing parishes to verify records, and enriching the collection with their own invaluable information.

First Diary

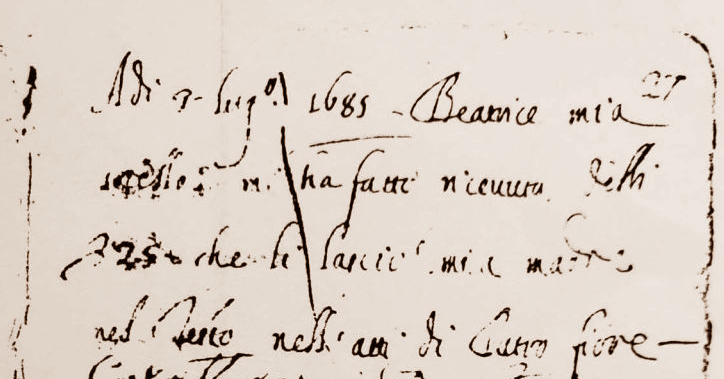

Beginning in 1678 and concluding in 1873, the first diary gives us an unvarnished tour of 195 years. According to the Preamble, it was written by Antonio (1817-1876), who was both a doctor of medicine and law. Antonio’s early entries were based on the original family diary kept by Marcantonio (1655-1714), which he began in 1678. Marcantonio writes in the first person, but Antonio mainly writes in the third.

The exact reasons for starting to write are unclear.

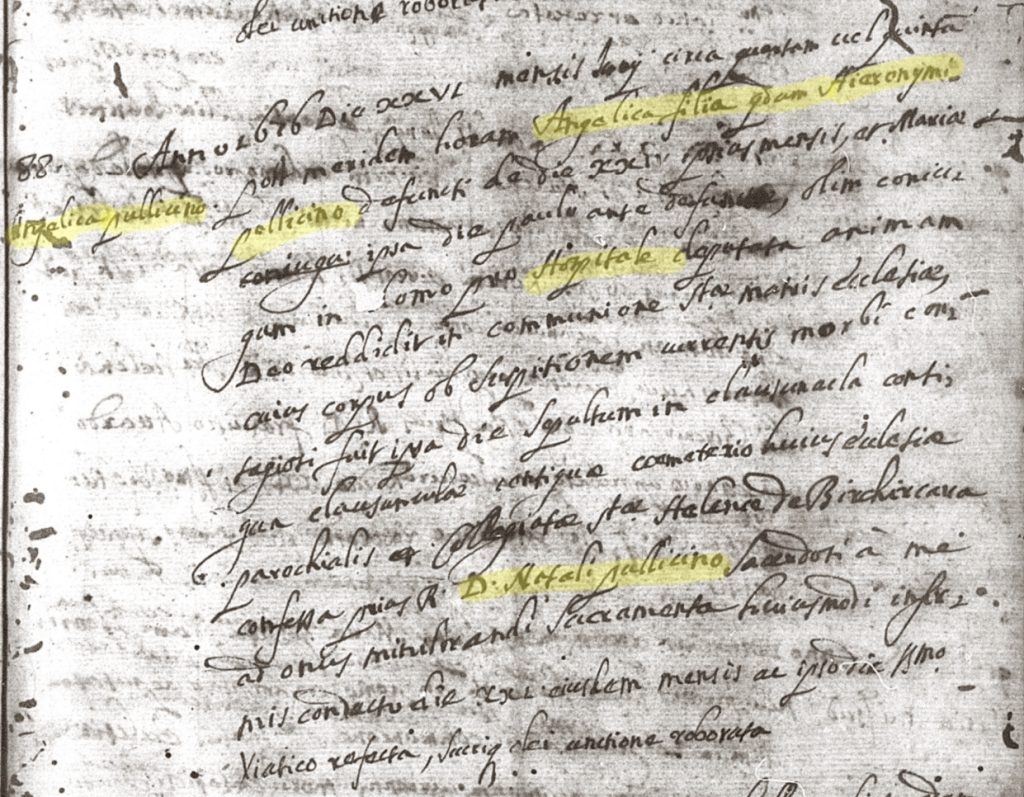

One theory is that the preceding two years had an effect on Marcantonio. The year 1676 was horrendous because of the spread of the bubonic plague, the worst in Malta’s history. Around 11,300 deaths were recorded, out of a population of around 60,000. Church gatherings stopped, people tried to move away from towns, and temporary isolation hospitals were set up. People were buried hastily in special cemeteries. Funeral practices became abbreviated. Many asked for penances increased their religious observance.

In Birkirkara the plague arrived in March, and several Pullicinos are recorded as having died of the plague. Marcantonio’s brother, Don Natale, administered last rites. We find entries for a certain Heironyma Pullicino’s death in June, and other relatives, who do not form part of our lineage (Minichella, Angelica, Maria, Johnella etc.).

The devastating effects of the 1676 plague may have given the 21 year old Marcantonio an experience of the imperamence of life. He was a new notary and he may have realised the importance of records in a changing world.

The Second Diary

The second diary overlaps somewhat beginning in 1814 and ending in 1968. The death of the first diarist of the second diary, Don Paolo in 1890, separates this latter diary into two distinct sub-segments: 1814-1889 and 1911-1968.

The second diary ends with a clear focus on Sir Philip Pullicino and Lady Maude.

General historical context

Living conditions

It is hard for us to understand how basic living conditions were for the Pullicinos in the early days. Here are some interesting technological advancements they experienced:

- The printing press, invented by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century, made its way to Malta in the 17th century. The Pullicinos obviously benefitted, as they belonged to a social class that valued education. Personal records, like the diaries, were handwritten and this form of communication suffers from fading and poor legibility.

- Indoor plumbing was probably non-existent for most of the first diary. We have forgotten what it was like to use a chamber pot, but our ancestors were very familiar with them. Toilet paper was not invented until the 1850s.

- Homes were lit by candles or oil lamps. This form of lighting was often unreliable and posed a significant fire risk.

- Glass windows were not usual in homes until the industrial revolution in the 1830s. Most homes would have used shutters.

- Storms were a significant risk to travel by ship and could delay journeys significantly. News did not travel fast. Malta to Rome could have taken 2 to 3 weeks.

- The rise of ledgers and contracts provided stability to commercial ventures. The notarial and legal class expanded, and our family was part of this change.

Population of the Maltese Islands

Malta was a small community that was closely interconnected socially. By the way, in this table you can see the effect of the 1676 Plague.

| Year | Malta | Gozo | The Order | Maltese Islands |

| 1530 | 25,000 | |||

| 1590 | 27,000 | 1,864 | 3,426 | 32,290 |

| 1614 | 38,429 | 2,655 | 41,084 | |

| 1632 | 49,866 | 1,884 | 3,648 | 51,750 |

| 1658 | 46,150 | 3,923 | 50,073 | |

| 1676 | 4,438 | 60,000 | ||

| 1680 | 43,800 | 5,700 | 49,500 | |

| 1736/40 | 58,435 | 7,929 | 66,364 | |

| 1798 | 90,000 | 24,000 | 114,000 |

British rule

From 1813, Malta was a British colony, a period marked by reorientation to a rising Empire. For example, there was a legal upheaval as British common law principles started to overlay the existing Maltese legal system. This period also saw modernisation and development of living conditions under British rule. The Pullicinos witnessed

- the foundation of the University of Malta: the decree constituting the University was signed by the Knights in 1769, however the University and other schools were significantly reorganised by the British in the 1830s.

- The introduction of compulsory primary education in 1868. Don Paulo was involved with that reform.

- The construction of the significant fortifications seems to have been ongoing under both the Knights and the British.

- Gas street lamps began to appear Valletta in the 1850s and came to Sliema around 1896. Electricity first appeared in Malta in 1882 and quickly took over from gas for home lighting.

- Over time Malta saw improvements in public health and sanitation off a very low base. Untreated sewage was a major problem in early 1800s.

- Valletta was an architectural marvel, and the British continued, with for example the construction of the Royal Opera House (1862-1866).

The diary notes family members in various roles such as Assessor, Judge, Doctor of Jurisprudence, Advocate, Professor, and Director of Primary Schools, demonstrating their diverse involvement in society.

Dedication to God and the Church

The diaries reveal the Pullicino family’s contributions to their community through public service, donations and devotion to the Catholic Church. The importance of Church life both from a social and spiritual perspective is hard to underestimate.

Disease and death

The diaries do not shy away from the harsh realities of life either.

Disease outbreaks, including a severe one in 1837, were common during this time. For example, it’s clear from the diary entries that mortality, especially child mortality, was a prevalent part of life.

- In one entry the family suffers the loss of two year old Gabriele Saverio from typhoid and rabies, in 1725.

- In another, the 1865 entry about the death of Paolino, the son of Dr. Filippo Pullicino, due to cholera.

Cholera, a bacterial disease spread through contaminated water, was not properly understood until Robert Koch identified the causative bacterium in the 1890s. Various other fatal conditions are mentioned in the diaries —meningitis, cerebral hemorrhage, heart disease, and convulsive attacks—likely stem from bacterial diseases now treatable with modern medicine.

Birth was always a risky affair. Operations such as caesarian sections almost inevitably meant death for the mother, either through blood loss or infection afterwards.